Investing in China: Weighing the Risks and Opportunities

Disclosure

Sources for all charts: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023 and World Economic Outlook Update, July 2023, September 2023.

This material is provided for informational purposes only and contains no investment advice or recommendations to buy or sell any specific securities. All investments carry risk and because the Chautauqua International and Global Growth equities strategies invest in foreign securities, which involve additional risks such as currency rate fluctuations and the potential for political and economic instability, and different and sometimes less strict financial reporting standards and regulations. They may also hold fewer securities than other strategies, which increases the risk and volatility because each investment has a greater effect on the overall performance. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This commentary represents portfolio management views and portfolio holdings as of 06/30/23. Those views and portfolio holdings are subject to change without notice. The specific securities identified do not represent all the securities purchased, sold or held for accounts and you should not assume these securities were or will be profitable.

The MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. Index®. Is a free float-adjusted market capitalization weighted index that is designed to capture large- and mid-cap stocks across 22 of 23 developed markets countries, excluding the United States, and 24 emerging markets countries. The MSCI ACWI Index® is a free float-adjusted market capitalization weighted index that is designed to represent performance of the full opportunity set of large- and mid-cap stocks across 23 developed and 24 emerging markets, including the United States. Indices are unmanaged and direct investment is not possible.

The MSCI information may only be used for your internal use, may not be reproduced, or disseminated in any form and may not be used as a basis for or a component of any financial instruments or products or indices. None of the MSCI information is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such. Historical data and analysis should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance analysis, forecast or prediction. The MSCI information is provided on an “as is” basis and the user of this information assumes the entire risk of any use made of this information. MSCI, each of its affiliates and each other person involved in or related to compiling, computing or creating any MSCI information (collectively, the “MSCI Parties”) expressly disclaims all warranties (including, without limitation, any warranties or originality, accuracy, completeness, timeliness, non-infringement, merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose) with respect to this information. Without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall any MSCI Party have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, punitive, consequential (including, without limitation, lost profits) or any other damages. (www.msci.com)

For additional important information about the fees, expenses, risks and terms of investment advisory accounts at Baird, please review Baird’s Form ADV Brochure, which can be obtained from your financial advisor and should be read carefully before opening an investment advisory account.

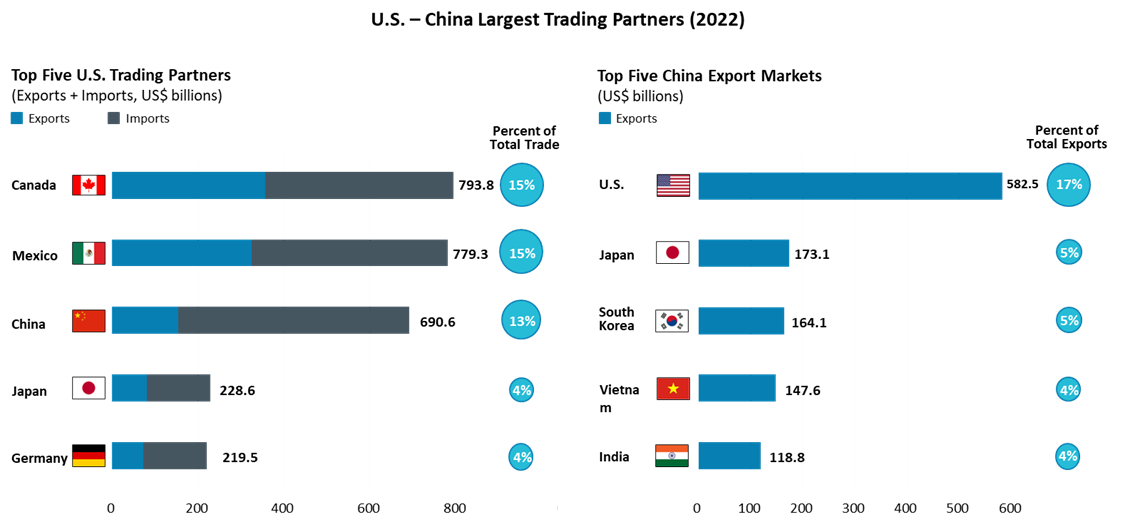

©2023 Robert W. Baird & Co. Incorporated. First use: 09/2023

1Peak China. (2023, August 20). The New York Times.

2Mauboussin, Michael J. (2009). Think Twice: Harnessing the Power of Counterintuition (pp 1-16). Harvard Business Press.

3Allison, Graham. (2015, September 24). The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/09/united-states-china-war-thucydides-trap/406756/

4According to the Annual Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community (Office of the Director of National Intelligence) published on February 6, 2023, “Beijing is working to meet its goal of fielding a military by 2027 designed to deter U.S. intervention in a future cross-Strait crisis”, p. 7; In testimony before the House Armed Services Committee on March 29, 2023, Defense Secretary Llyod Austin said in a response to questions about whether and how soon China would invade Taiwan that “I don’t think an attack on Taiwan is imminent, nor inevitable.” Source: Wadhams, N. & Trion, R. (2023, March 29). Austin Sees No Sign Chinese Invasion of Taiwan is Imminent. Bloomberg.

5Case File | Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. (n.d.) Harvard Kennedy School – Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. https://www.belfercenter.org/programs/thucydidess-trap/thucydidess-trap-case-file

6Allison, Graham, Kiersznowski, Nathalie & Fitzek, Charlotte. (March 2022). The Great Economic Rivalry. Harvard Kennedy School – Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, p. 31. https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/great-economic-rivalry-china-vs-us

7Wikipedia contributors. (2023). Foreign Trade of the Soviet Union. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foreign_trade_of_the_Soviet_Union

8Trade defined as the sum of goods exports to China and goods imports from China. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) – U.S. Department of Commerce. (2023, February 7). U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services December and Annual 2022 [Press release]. https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2023-02/trad1222.pdf – Note that in addition to trade in goods, U.S.-China trade in services was $68 billion in 2022. Final 2022 services trade data was released separately by the BEA on July 6, 2023.

9The US-China Business Council. (2023). US Exports to China: Goods and Services Exports to China and the Jobs They Support, by State and Congressional District, p. 1. https://www.uschina.org/reports/us-exports-china-2023-0

10Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, and India were China’s #2-#5 export markets in 2022, excluding Hong Kong. Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics. https://data.imf.org/?sk=9d6028d4-f14a-464c-a2f2-59b2cd424b85

11Advanced Democratic Economies (ADEs) are liberal democracies with advanced economies. ADEs defined as the Group of Seven (G7) countries – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States – plus Australia, Norway, Republic of Korea, and the European Union. Source: Kramer, Franklin D. (February 2023). China and the New Globalization. Atlantic Council | Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, p. 2. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/china-and-the-new-globalization/

12Cronin, Richard. (2022, August 16). Semiconductors and Taiwan’s “Silicon Shield.” Stimson Center. https://www.stimson.org/2022/semiconductors-and-taiwans-silicon-shield/

13Lee, Y., Shirouzu, N., & Lague, D. (2021, December 27). Silicon Fortress – T-DAY – The Battle for Taiwan. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/taiwan-china-chips/

14Crawford, A., Dillard, J., Fouquet, H., & Reynolds, I. (2021, January 25). The World is Dangerously Dependent on Taiwan for Semiconductors. Bloomberg.

15Varley, K. (2022, August 2). Taiwan Tensions Raise Risks in One of the Busiest Shipping Lanes. Bloomberg.

16Wintour, P. (2023, April 25). If China invaded Taiwan it would destroy world trade, says James Cleverly. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/25/if-china-invaded-taiwan-it-would-destroy-world-trade-says-james-cleverly

17Compert, David C., Cevallos, Astrid S. & Garafola, Cristina L. (2016). War with China: Thinking Through the Unthinkable. RAND Corporation, pp. 41-50, 85-88. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1140.html; Based on the work of Reuven Glick and Alan M. Taylor, “Collateral Damage: Trade Disruption and the Economic Impact of War” (2010) which studied falls in bilateral trade between combatants and corresponding declines domestic consumption in World War I and World War II, RAND assumes that U.S.-China bilateral trade drops by 90% and domestic consumption falls by 4% in each country. A potential conflict’s GDP impact is asymmetrically higher on China as RAND assumes that China also suffers an 80% decline in East Asia regional trade and its other global trade falls by 50% because of the postulated “war zone” effect on seaborne trade in the Western Pacific (~90% of China’s trade is seaborne). The high-end of U.S. estimated GDP loss includes an anticipated decline in trade with other Asian countries due to the “war zone” effect on seaborne trade. China’s estimated 25-35% decline in GDP can compared with Germany’s 29% decline in real GDP during World War I, when Germany itself was spared heavy damage.

18Rich, B. R. (n.d.). The Great Recession. Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-recession-of-200709#:~:text=Beyond%20its%20duration%2C%20the%20Great,data%20as%20of%20October%202013) .

19Culver, John. (2022, October 3). How We Would Know When China Is Preparing to Invade Taiwan. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/10/03/how-we-would-know-when-china-is-preparing-to-invade-taiwan-pub-88053

20DiPippo, Gerard. (2022, August 16). Economic Indicators of Chinese Military Action Against Taiwan. Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/economic-indicators-chinese-military-action-against-taiwan

21America v China – It’s Worse Than You Think (2023, April 1-7). The Economist.

22Martin, E. (2023, April 6). IMF Warns Five-Year Global Growth Outlook Weakest Since 1990. Bloomberg.

23Qi, L. (2023, August 19-20). China’s Fertility Rate Dropped Sharply, Report Shows. The Wall Street Journal.

24O’Hanlon, Michael E. (2023, April 24). China’s Shrinking Population and Constraints on Its Future Power. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-shrinking-population-and-constraints-on-its-future-power/

25Wei, L., & Xie, S. Y. (2023, August 21). China’s 40-Year Boom Is Over Raising Fears of Extended Slump. The Wall Street Journal.

26Bloomberg Economics. (2023, August 21). CHINA INSIGHT: Rescue – Or Risk Crisis on Debt Too Big to Manage. Source: Bloomberg.

27IBID.

28Our sole holding with net debt had a Net Debt/EBITDA ratio of 0.58x at the end of 2022. Source: Bloomberg.

29Liu, Z. Z., & Stemp, D. (2023, March 21). The PBoC Props Up China’s Housing Market. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/pboc-props-chinas-housing-market#:~:text=Kenneth%20Rogoff%20estimated%20that%20the,before%20the%20global%20financial%20crisis

30IBID

31Confidence Trap. (2023, June 24-30). The Economist.

32IBID

33Ahya, Chetan. (2023, August 8). How China could avoid a 1990s Japan situation. Morgan Stanley Research.

34Source: The World Bank.

35Ahya, Chetan. (2023, August 8).

36Alloway, T., & Weisenthal, J. (2023, July 10). Richard Koo Is Getting Famous in China as Debt Problems Grow. Bloomberg.

37International Monetary Fund. (April 2023). World Economic Outlook.

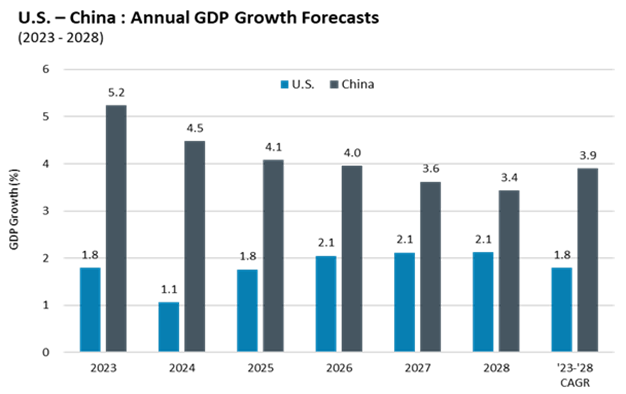

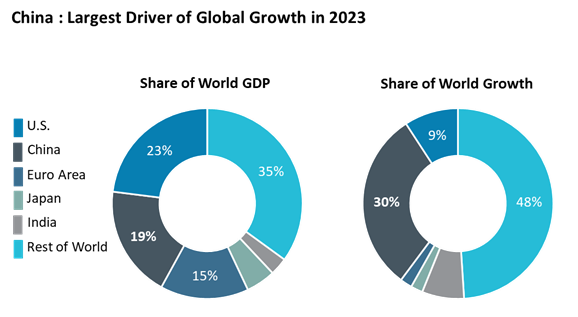

38Tanzi, A. (2023, April 17). China to Be Top World Growth Source in Next Five Years, IMF Says. Bloomberg.

39Wei, L., & Xie, S. Y. (2023, August 21). China’s 40-Year Boom Is Over Raising Fears of Extended Slump. The Wall Street Journal.

40Swedroe, Larry. (2022, October 5). Is There a Link Between GDP Growth and Emerging Market Returns. The Evidence Based Investor (TEBI).

41Nikkei 225 Index peaked on December 29, 1989, at 38,916. On August 31, 2023, the Nikkei 225 Index closed at 32,619. Source: Bloomberg.

4212-month forward PE for the Bloomberg China Large-Mid Index (CN), S&P 500 Index (SPX), Bloomberg World ex-China Index (WORLDXC) and Bloomberg Emerging Markets ex-China (EMXCN) as of 8/31/23. CN Index 12-month forward PE discounts relative to the SPX, WORLDXC and EMXCN indices are at the high-end of their historical ranges since December 2009 – 98th, 88th and 87th percentiles, respectively. Source: Bloomberg.

43From December 29, 1989, to August 31, 2023, in U.S. dollar terms, Keyence’s total return of 5,227% (12.5% annualized) compares to a total return of 2,451% (10.1% annualized) for the S&P 500. Source: Bloomberg.

44Huang, Z., Zhang, J. and Zheng, S. (2023, July 24). China’s Tech Crackdown is Ending. What Does It Mean? Bloomberg; (2023, August 25). Everything China Is Doing to Juice Its Flagging Economy. Bloomberg.

45Huang, T., & Lardy, N. (2023, January 10). Can China revive growth through private consumption? Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/can-china-revive-growth-through-private-consumption

46Allison, Graham, Kiersznowski, Nathalie & Fitzek, Charlotte. (March 2022). The Great Economic Rivalry. Harvard Kennedy School – Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, p. 42.

47Health spending as percent of GDP by country | TheGlobalEconomy.com. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/health_spending_as_percent_of_gdp/

The Japan analogy has stoked fears that China could fall into a debt-deflation loop where debt to GDP keeps rising even as debt growth slows and per capital income growth stagnates. However, there are several key differences that improve China’s prospects relative to 1990s Japan.33 First, the rise in Chinese property prices was not as steep as Japan’s. China’s ratio of property values to GDP peaked at 260% of GDP after rising from 170% in 2014. In Japan, land values peaked at 560% of GDP in 1990 before falling back to 394% by 1994. Second, China still has much higher potential growth compared with Japan in the early 1990s. China’s 2022 per capital income of $12,72034 is less than 20% of the U.S. level, implying that China still has significant growth headroom. In contrast, Japan’s per capital income was nearly 20% higher than that of the U.S. in 1990.35 Finally, Chinese policy makers have the distinct advantage of learning from the mistakes of Japan whose initial policy stance was too restrictive (which led to a strong Yen and eroded the competitiveness of the corporate sector), too slow and lacked coordination of fiscal and monetary stimulus.36

The Japan analogy has stoked fears that China could fall into a debt-deflation loop where debt to GDP keeps rising even as debt growth slows and per capital income growth stagnates. However, there are several key differences that improve China’s prospects relative to 1990s Japan.33 First, the rise in Chinese property prices was not as steep as Japan’s. China’s ratio of property values to GDP peaked at 260% of GDP after rising from 170% in 2014. In Japan, land values peaked at 560% of GDP in 1990 before falling back to 394% by 1994. Second, China still has much higher potential growth compared with Japan in the early 1990s. China’s 2022 per capital income of $12,72034 is less than 20% of the U.S. level, implying that China still has significant growth headroom. In contrast, Japan’s per capital income was nearly 20% higher than that of the U.S. in 1990.35 Finally, Chinese policy makers have the distinct advantage of learning from the mistakes of Japan whose initial policy stance was too restrictive (which led to a strong Yen and eroded the competitiveness of the corporate sector), too slow and lacked coordination of fiscal and monetary stimulus.36